Policies that worked for two decades are doing less well in the post-2001 world.

In the New York Times, Ross Douthat has a thoughtful column that uses Oren Cass’s provocative new book, The Once and Future Worker, as a springboard for thinking about the future of conservative reform. Cass, Douthat argues, represents a faction within conservatism that thinks the neoliberal order needs substantive and deep reforms. Other conservatives are much more wary of a radical critique of neoliberalism: They “are willing to tinker with work-and-family policy but worry that to make any major concession to globalization’s critics puts far too much at risk.”

One of the difficulties of debating the fate of the neoliberal order is that any policy regime leads to implications that may end up undermining this regime. The shift toward more market-oriented policies in the late 1970s rolled back government regulations and encouraged the freer flow of labor and capital across national boundaries. There’s a plausible case to be made that such reforms bore fruit in the 1980s and 1990s: There was renewed economic growth during this period, the Soviet Union collapsed, and many impoverished parts of the world saw a radical improvement in living standards.

However, there is also some evidence that this policy regime faltered after 2001. Since then, American economic growth has been cut in about half; a slump in growth can be seen both overall and on the per capita level, which suggests that the sluggishness is not simply because of diminished population growth. As Cass and others (including Nicholas Eberstadt in a bracing Commentary article) have noted, some social and economic indicators have nosedived over the past two decades. As the United States has experienced economic disruption and interior division, its geopolitical competitors have gained a larger footprint in world affairs. Many defenders of the current iteration of globalization recoil in horror at the rise of populism on the right and the left, but this rise is a consequence of the tumult caused by high neoliberalism.

In this time of disruption, What Ifs: The Nineties Edition can be as comforting as a down blanket in a storm. What if the Maastricht Treaty (which established the euro) had been less ambitious? What if the moderate immigration recommendations of the Jordan Commission had not been defeated by a coalition of corporate and identity-politics activists (presaging the increasing dominance of such a coalition in our own time)? What if financial deregulation in the 1990s had been more cautious in order to prevent the hyper-consolidation of the nation’s banking system? What if the People’s Republic of China had not been made a full member of the World Trade Organization? Certain tendencies incipient in the pre-1989 policy regime became more fully realized, with radical implications.

Of course, such questions are a parlor game, and blankets are no substitute for forward-looking policies. The policy decisions of the 1990s radically transformed American economic life and created the major questions facing us today. Now the issue is not whether to prevent mass financial consolidation but whether to reverse it — and, if so, how. Nearly two decades of economic stagnation have diminished the United States’ ability to project power abroad; if it had grown at historical norms since 2001, it would be a much bigger chunk of the global economy than it is now. In Europe, the increasing ambitions of Brussels have weakened the ability of the EU to follow a middle way (as an alliance of states with common interests but distinctive sovereignties); instead, some Europeans feel that they are facing a choice between exit and submission to a transnational federation. (There are, of course, other choices, but many EU policymakers are pushing this particular binary.)

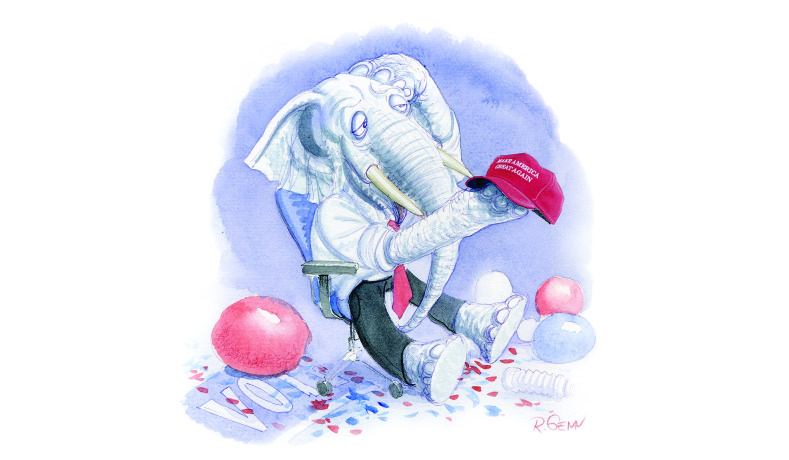

The trends that neoliberalism has unleashed in much of the West include increased cultural anxiety, diminished economic growth, and an explosion of political parties on extreme ends of the political spectrum. If these trends continue, the post-1989 geopolitical order (upon which neoliberalism depends) could continue to deteriorate. What replaces it might end up being amenable to neoliberal interests, or it might not. In light of the potential for more severe disruption, a case can be made that substantive reforms now could end up being a stabilizing choice. These reforms would very likely include adjustments to immigration and trade, but they could also include domestic-policy reforms (from updates to the safety net to pro-worker policies to anti-monopoly efforts).

In thinking about the scope of this reform, history can offer some insight. For all the narratives that position Ronald Reagan as a founder of the neoliberal order, his actual record of governance shows that he was far from a doctrinaire neoliberal. He inveighed against “protectionism” but also established import quotas on Japanese automobiles. Despite his invocation of the “shining city” with a door “open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here,” the legal-immigration system was much more restrictive in his time than it is in ours; about half as many green cards were given out in the 1980s as in recent years. His version of entitlement reform involved a tax hike to make Social Security sustainable.

One might disagree with these policy choices, but they show Reagan’s awareness of the need to maintain some social and economic consensus in the face of market disruptions. Reagan could not govern through market ideology alone. This responsiveness is part of what made Reagan successful as a politician and might be contrasted with the torpor of the recent GOP legislative program. This history might also remind Republicans that the center-right policy menu is far broader than some ideologues might argue, as the examples of Eisenhower, Coolidge, and Lincoln indicate as well. Renewing national integrity may be a way of placing future prosperity on firmer ground.