Hundreds of thousands of homes in the Southeast may have had their wells inundated by record-level floodwater resulting from major hurricanes this year, yet only a fraction have been tested for harmful contaminants.

That’s because North and South Carolina, Florida and Georgia — like most other states — don’t require routine testing of private wells. Lawmakers have long been hesitant to put requirements on wells on private property.

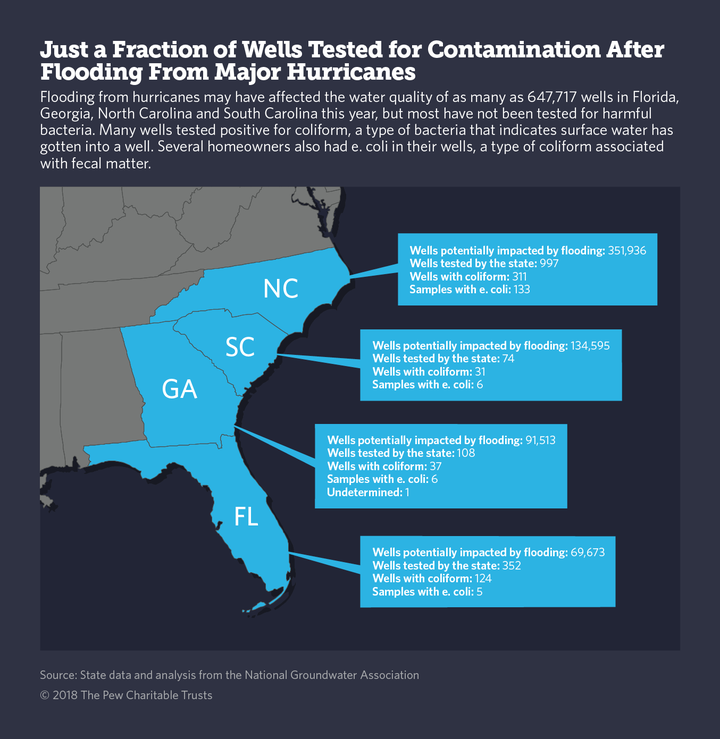

Hurricanes Florence and Michael alone dumped more than 30 inches of rain on some areas stretching from Florida to North Carolina, creating a toxic soup that may have overwhelmed nearly 650,000 wells, according to estimates from the National Groundwater Association, an alliance of groundwater experts based in Westerville, Ohio.

More than 30 above-ground hog lagoons overflowed in North Carolina after Hurricane Florence in September, sending pig waste into water inundating surrounding communities. Floodwater from Florence and Michael also contained agricultural runoff, fuel and other contaminants that can seep into the aquifer or flow into man-made wells through their ground-level ventilation systems.

Without data, though, scientists and public health officials won’t know the full impact of the flooding on private wells.

Public health departments across the four states offered free well water tests to anyone affected by the hurricanes. Yet fewer than a thousand homeowners opted for water quality tests in each state, health departments said.

After a natural disaster, relatively few people opt to get their water tested for contamination, often because they don’t know there may be a problem or are afraid the results might hurt their home value. But even those who do may have never done so before, leaving many well water drinkers unable to pinpoint how long they’ve been drinking bacteria-tainted water or the source of the contamination.

This is a particularly acute problem in North Carolina, where 2.4 million people rely on wells for their drinking water — the fifth-highest number in the nation, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, and about a fifth of the state’s population.

The state also is home to a high concentration of open pits filled with hog or chicken waste or coal ash, the residue from coal-fired power plants. That is joined by standard agricultural runoff, fuel and other contaminants picked up by floodwater.

“There’s bacteria all over the ground,” said Wilson Mize, an environmental health specialist with the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services’ public health division. As waters rise, they inundate the above-ground portion of the well, which includes a small vent. “If you have over a foot of flooding, even on a perfectly constructed well, water is going to find its way in.”

A post-Florence recovery recommendation report from North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, said the state lab anticipated running 1,650 water tests, at a cost to the state of $36 each, but under 1,000 samples had been tested as of Nov. 30.

Results from households that took advantage of the free testing show that in each of the four states, more than 30 percent of wells tested positive for coliform, bacteria that indicate surface water has entered a well. And in North Carolina, tests found that 13 percent of wells were contaminated with e. coli, a type of coliform associated with fecal matter.

That’s compared with about 2 percent of wells that typically test positive for e. coli or other coliform in the Tar Heel State, the health department said.

Travis Long/The News & Observer via AP

North Carolina in 2008 began requiring new wells get tested shortly after they are constructed. South Carolina offers free — but voluntary — well water testing when a new well is constructed. Testing only at construction leaves older wells, potentially some of the most vulnerable to contamination, untested. Florida and Georgia have no testing requirements whatsoever.

“It’s not a requirement under the law,” said Chris Rustin, the director of environmental health at Georgia’s Department of Public Health, adding that the state’s lack of regulations is not unusual. “In most states, it’s totally up to the homeowner to have the well samples and ensure water quality.”

Georgia sampled 108 wells after Hurricane Michael hit in October, of which 43 percent were positive for coliform.

Merritt Partridge, vice president of Partridge Well Drilling in Jacksonville, Florida, said his business usually gets more calls after a hurricane, often from people saying they heard on the news that their well might be contaminated. When he assures them that their well was unlikely to be affected unless their area was flooded, the tone of the call often changes.

“We say it’s always wise to get it tested, it’s always good to know what’s in your water, hurricane or not,” Partridge said, “But that response almost always takes the edge off.”

“Then people say, ‘Well how much is it? Is it worth it? I’ve been drinking this water for the last 20 years,’” Partridge said, speaking of his experience after Hurricane Irma last year. “Some people are drinking water that they shouldn’t be, but they have no idea.”

Testing a well isn’t very expensive, but a basic chlorine treatment that kills bacteria can cost around $500, he said.

North Carolina was at greater risk of fecal contamination in wells than other states, in part because of the heavy rains that preceded Hurricane Florence, said Chuck Job, regulatory affairs manager with the groundwater association. He analyzed rainfall patterns from storms for the group to estimate how many wells were affected.

Casey Toth/The News & Observer via AP

Most people with wells also rely on septic systems, which filter and store household waste underground. The two systems typically don’t interact, Job said, but an already-saturated ground covered with floodwater might raise the water table, leaving the two systems “hydrologically connected.”

But there could be other contributors of e. coli. At least 33 North Carolina hog lagoons overflowed because of rain from Hurricane Florence, according to the state’s Department of Environmental Quality.

“North Carolina’s swine industry is concentrated in a part of the state uniquely vulnerable to its waste management practices,” said Will Hendrick, a North Carolina-based staff attorney for the Waterkeeper Alliance, an environmental advocacy group. The hog lagoons are located mainly along the coastal plains, in an area with a high water table, high poverty rates and a large number of wells.

He pointed to a 2015 Johns Hopkins study that used genetic markers found in swine waste to determine hog lagoons were the source of contamination in nearby surface waters.

But some experts think hog lagoons are unlikely to be the source of contamination. Michael Burchell, an associate professor at North Carolina State University, joined scientists from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and Virginia Tech, and the state, in testing well water for free for North Carolina residents affected by the hurricane.

The three universities targeted well users in areas with low testing rates, typically in communities with higher poverty rates and larger minority populations. Nearly a third of the 140 wells tested contained coliform.

Floods mobilize all kinds of waste, Burchell said, including that of wild animals and pets. Usually flushing the well or using bleach or UV lights will solve problems tied to flooding.

Andrew George, the community engagement coordinator with the UNC Institute for the Environment, went door to door with community leaders talking to people about the free testing being offered by the universities.

Many homeowners are afraid to test their wells because of what they might find, he said. “People don’t want to hurt their property value.”

Although more than 130 wells tested by the North Carolina health department were contaminated with e. coli, it’s not clear anyone got sick from drinking bad well water, though many stomach illnesses go unreported to county health departments.

Hurricane Florence contributed to some of the worst flooding Smith has seen. Even in a county defined by its swampland, most of the land became submerged as rivers and lakes overflowed.

“There were several of our towns that were like islands during the storm,” she said. “We were just cut off.”

Hendricks said the Waterkeeper Alliance and other environmental groups in North Carolina are pushing for the state to include funding to help people pay to get their wells tested more regularly as part of a hurricane recovery package.

Cooper outlined a proposal that estimated $100 million was needed to repair damage to the state’s public water and sewer infrastructure but was silent on funding for well water tests.

In October, the North Carolina Legislature set aside nearly $800 million for recovery efforts. But Gov. Cooper said in his proposal that the funding from the legislature won’t be enough to cover state may need to spend $1.5 billion “over several years,” reported The News & Observer.